End Fittings: How Pipe Differs From Tube

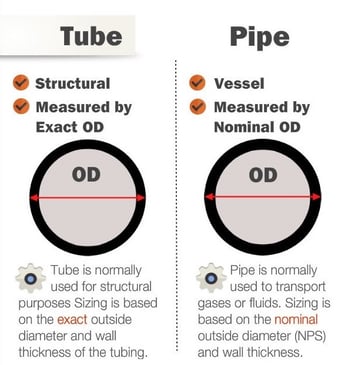

When you look at general fittings classifications, pipe fittings are defined as a part used in a piping system: for changing direction, branching, or for change of pipe diameter. Tube fittings consist of tubing and the fittings that connect them. While the definitions sound similar, important differences exist based on how pipe and tube are measured and sized, and the different applications in which they are used.

Measurement and Sizing

Pipe

In the early 1900s, only three pipe thicknesses existed for pipe, which were then cast in 2 pieces from wrought iron: STD (standard weight), which later became known as Schedule 40 pipe; XS (extra-strong), which later became known as Schedule 80 pipe; and XXS (double extra-strong), which later became known as Schedule 160 pipe. After WWII, manufacturers began making pipes out of stainless steel, allowing for thinner walls and lighter weights. Thus Schedule 5 and Schedule 10 pipe were introduced.

- Process piping systems are typically Schedule 40, 80, or sometimes 160

- NPS (Nominal Pipe Size) is a size standard established by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), and should NOT be confused with the various thread standards such as NPT, NPSM, et al.

- The metric equivalent is called DN or "diametre nominel“, measured in mm.

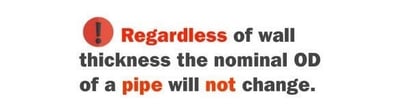

Pipe sizing can be confusing because when you measure the outside diameter (O.D.) of a 4″ pipe, it’s actually 4.5″. Every pipe O.D. is somewhat larger than the labeled size until you reach 14″, and then the schedule pipe size is actually the outside diameter size.

Originally, schedule pipe was labeled by the inside diameter size, but as the constructed material and wall thicknesses evolved, the inside diameter changed. The outside diameter stayed the same so it could mate with existing older pipe. Now, in order to have some form of consistency, pipe is ordered by the nominal diameter measurement (example: 4″ NPS), which is a fixed value, then by schedule (example: Schedule 40), which determines the thickness of the wall.

Tube

When you measure the outside diameter of tubing, you get the true measurement of the tube. A 4″ O.D. tube is exactly that, a tube that is 4 inches across the outside diameter. Tubing wall thickness is typically specified by the thickness in thousands of an inch (e.g. .035”, .049”, etc.) while metric tubing size and wall thickness is measured in mm. Tubing also generally has a smoother surface finish (both ID and OD), which permits the transfer of sanitary/food grade material and facilitates connections using tube fittings, which typically seat on the interior or exterior of the tube, e.g. JIC/SAE flared tube fittings.

The inside diameter of a tube depends on the wall thickness of the tube. The thickness is often specified as gauge (or sometimes gage). Interestingly, while the stated and measured OD’s of tubing are usually the same, copper tubing generally has a measured OD that is 1/8” larger than the stated OD. If in doubt, measure the ID and OD of the tube/pipe, then compare the results to pipe and tube dimension charts found in various reference materials. One such reference can be found here.

From an Application Standpoint

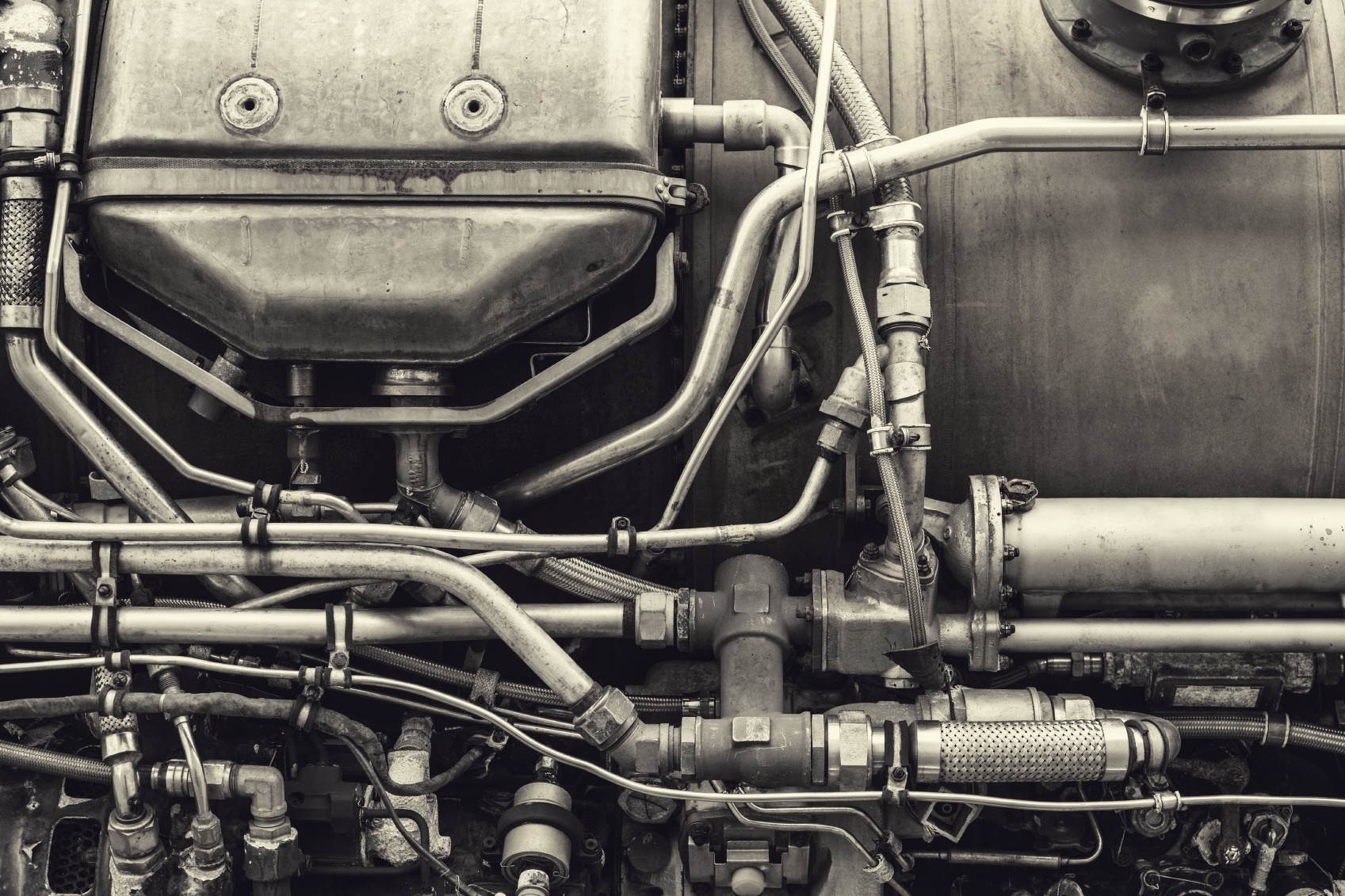

Pipe is generally used for the transfer of gas, liquids, chemicals, and steam in industrial plants and power utilities. Components like socket weld couplings are more common in piping systems where crevices are not a concern (crude oil, steam systems) and butt-weld fittings are more common in applications requiring corrosion resistance (chemical, pulp and paper, etc.).

Tubing is generally used for high-pressure hydraulic fluid systems, where metal-to-metal seals are preferred. These applications range from food-grade, pharmaceutical, semi-conductor and sanitary (e.g. “hygienic”) process systems, where polished surfaces prohibit bacterial growth. Tube bundles are also used in heat exchanger vessels to improve heat transfer properties. Since tubing has tighter tolerances than pipe, it is preferred for use in medical equipment and boiler tubes.

In the Bulk Material Handling industry, tube is typically used for items such as powders and pellets in a dilute phase conveying system. Pipe, on the other hand, is often used for abrasive materials or for dense phase conveying systems. They typically use Schedule 10, Schedule 40, and Schedule 80.

Final Considerations

It is important to remember the following:

- Each connection in a system is a potential leakage point

- Bent tubing may reduce the number of connections, facilitating installation

- Pipe elbows may increase turbulence in the system

- Both pipe and tubing are available as welded or seamless construction

- Seams are usually longitudinal, although some spirally-welded pipe is used in certain applications

If you need help deciding what fitting type is best for an intended application, do not hesitate to contact the Hose Master inside sales department at insidesales@hosemaster.com or 1-800-221-2319 or visit us at www.hosemaster.com, and we would be happy to help you determine the best end fitting option for your metal hoses.

About Frank Caprio

Frank Caprio is the Corporate Trainer/Major Market Specialist at Hose Master, LLC. He has more than 35 years of experience in hydraulic, industrial, metal hose and expansion joint products and applications, and is the “Dean” of Hose Master’s training program, Hose Master University. He is nationally recognized as a leading authority in metal hose, and has authored various articles for industry publications and become a sought-after source for industry facts and trends. Frank is a member of AIST, ASM International, and ASTM International and is on NAHAD’s Technical Committee for Corrugated Metal Hose.